Music

Lute Ensemble: Stanley Buetens Recordings 1964-1995 now available for download and streaming!

Over 50 years in the making, these are the previously unreleased recordings of Stanley Buetens with a variety of ensembles. He was working on finalizing this album before his death. Available in all the usual places. Click the link of your liking below.

In A Medieval Garden: Instrumental and Vocal Music of the Middle Ages and Renaissance

We are proud to finally re-release In A Medieval Garden after more than 40 years! A classic album of music spanning four centuries re-released in digital form for the first time. Wonderful instrumentation and vocals which will take you back in time more than 400 years. This is the stereo version. See below for CD version. Please leave reviews on any site you buy from! Originally released in 1967. This recording was originally recorded for Nonesuch Records and is released under license from Nonesuch Records.

We are proud to finally re-release In A Medieval Garden after more than 40 years! A classic album of music spanning four centuries re-released in digital form for the first time. Wonderful instrumentation and vocals which will take you back in time more than 400 years. This is the stereo version. See below for CD version. Please leave reviews on any site you buy from! Originally released in 1967. This recording was originally recorded for Nonesuch Records and is released under license from Nonesuch Records.

Stanley Buetens Lute Ensemble included:

Stanley Buetens | lute, tenor, director Martha Blackman | viols Roland Blow | recorders, krummhorns Diane Tramontini | soprano Linda Nied | recorders Catherine Liddell | lute, percussion Lawrence Selman | viol, percussion

Available at:

Bandcamp is slightly more expensive but allows you to download at CD quality if you wish.

Listen to samples from the album

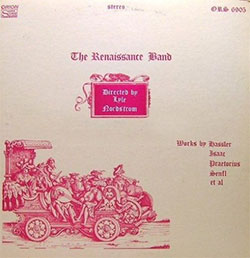

The Renaissance Band - Stanford University Collegium Musicum

Works by Hassler, Isaac, Praetorius, Senfl, et al

A very rare recording released only on LP in 1969. Though not available for sale, all tracks have been digitized for your listening pleasure below. THE RENAISSANCE BAND Lyle Nordstrom, Director TIMOTHY AARSET — Bass,recorders, crumhorns, rauschpfeife, alto dulcian, bass shawm DAVID BERRY — Crumhorn STANLEY BUETENS — Lute EDWIN A.HOPKINS — Recorders,bass flute, crumhorn,lute,bass gamba HERBERT MYERS — Recorders, lutes, crumhorns,treble shawm,viola da braccio, rackett,virginal LYLE NORDSTROM — Recorders, crumhorns, alto shawm, cornetto, rauschpfeife, kortholt,lute,bass gamba PATRICIA NORDSTROM — Recorders, crumhorn, tenor shawm, bass gamba NILE NORTON — Tenor PHILLIP WARREN — Tenor recorder, crumhorn, bass shawm, tenor gamba JOHN WINBIGLER — Baritone KARI WINDINGSTAD — Soprano

A very rare recording released only on LP in 1969. Though not available for sale, all tracks have been digitized for your listening pleasure below. THE RENAISSANCE BAND Lyle Nordstrom, Director TIMOTHY AARSET — Bass,recorders, crumhorns, rauschpfeife, alto dulcian, bass shawm DAVID BERRY — Crumhorn STANLEY BUETENS — Lute EDWIN A.HOPKINS — Recorders,bass flute, crumhorn,lute,bass gamba HERBERT MYERS — Recorders, lutes, crumhorns,treble shawm,viola da braccio, rackett,virginal LYLE NORDSTROM — Recorders, crumhorns, alto shawm, cornetto, rauschpfeife, kortholt,lute,bass gamba PATRICIA NORDSTROM — Recorders, crumhorn, tenor shawm, bass gamba NILE NORTON — Tenor PHILLIP WARREN — Tenor recorder, crumhorn, bass shawm, tenor gamba JOHN WINBIGLER — Baritone KARI WINDINGSTAD — Soprano

Information from the back cover of the record

Austro-German music occupied only a peripheral position in the history of music until the second half of the 15th century. With the appearance of the great songbook collections, especially the monumental Glogauer Liederbuch (1470), and the establishment of Emperor Maximilian’s Hofkapelle (1496), German music moved from the shadows. At the Emperor’s imperial courts in Vienna and Innsbruck, native German composers came into close contact with the ideals and techniques of the Flemish tradition. The smoother, sophisticated style which emerged from this contact relied more heavily on imitation and florid lines than had the angular and dissonant writing of the earlier 15th century. Maximilian’s Hofkapelle, considered one of the finest musical establishments of its time, was associated with at least three important composers. Heinrich Isaac, the most influential of the three, was appointed official composer to the court of Lorenzo the Magnificent in Florence. He was well trained in the techniques of Flemish composition, with its characteristic use of complex polyphonic lines woven around a cantus firmus, canon, and other imitative devices. Working with these materials, he was able to assimilate different styles with great ease, emerging as the first “international” composer — writing Italian frottole, French chansons and German lieder, all with the same apparent fluidity. His instrumental masterpiece, La la hö hö, seems on first hearing to be only a simple and lively work, but it has a subtly executed structure which, as in all great music, enhances the composition without being obviously heard. A simple eight note motive is taken through three distinct stages, each slightly more complex. Isaac strongly influenced his colleagues and students Paul Hofhaimer and Ludwig Senfl, particularly in the use of imitation. Hofhaimer, who was primarily attached to the court at Innsbruck, was known as the greatest organist of the time. Unfortunately, since the organ was almost entirely an improvisatory instrument during this period, little of the music survives. He was also, however, a fine composer of polyphonic lieder, and a good sampling of this music is extant. Mein Trauens is set in the phrygian mode, is one of the most plaintive and beautiful of the love-laments, a popular form in the Renaissance. Ludwig Senfl probably entered the Hofkapelle at its inception, as a choir boy. He became a student of Isaac and inherited Isaac’s position as court composer upon the master’s resignation. Although Senfl’s style bears the unmistakable marks of Isaac’s influence, his writing retains a much more stark and dramatic Germanic flavor. He had a gift for warm, flowing melody and rhythmic vitality which, when combined with his mastery of counterpoint and contrapuntal devices, rarely failed to produce a work of surpassing beauty.

Most of Senfl’s lieder employ the usual tenor cantus firmus, but his Jove of counterpoint frequently led him to put this cantus firmus into canon, as is the case with three of the selections on this record: the two versions of Es taget vor dem Walde, and Wann ich des Morgens frueh aufsteh’. Ach Elselein, liebes Elselein mein is one of the few instances in which Senfl used a homorhythmic setting, putting the cantus firmus in the top voice. His quodlibet, combining these three cantus firmi, displays a great contrapuntal skill without distracting attention from the piece as a whole.

Erasmus Lapicida is one of many shadowy figures found in Renaissance musical history. He can be traced to Austria as late as 1544, but was certainly known outside the Germanic realm, as some of his compositions were published by Petrucci in Venice as early as 1503. His setting of the Tander naken melody (one of the most popular cantus firmi for the Flemish composers) is certainly one of the loveliest compositions from the early 16th century.

In the later 16th century, there is almost no emphasis on the use of a cantus firmus. Instead, composers relied upon equal voices, in imitation, or a homorhythmic style of writing which placed the melodic emphasis in the top voice. These styles were often used alternately within the same piece, as is the case with all three of the madrigals found on this recording: Ihr Musici, frisch auf!, Ich weiss ein Maedlein huebsch und fein, and Bernard Schmidt’s florid keyboard intabulation of the Italian Domenico Ferrabosco’s Io mi son giovanetta. Hassler’s Ihr Musici also reflects the influence of his Venetian instructor Giovanni Gabrieli. The frequent polychoric effects give the impression of a double choir,but strictly speaking,the piece is only a six-voice madrigal. It was quite a common practice in this period to play madrigals on instruments,and this liberty has been taken here.

Dance, as one of the primary means of exercise and courtly entertainment, played an important role in the social life of the Renaissance courts. A culmination of the multitude of 16th century dance publications is found in Michael Praetorius’ Terpsichore, published in 1612. This huge collection contains well over 400 dances,many of them, especially the bransles, arranged into long suites These bransles, deriving from peasant dances,were danced in a circle or a line, not unlike folk dances (the hora, for example) still popular today. Frequently a number of different types of bransles were included in one suite,to be used to open the dancing at a festival. The Bransle de la Royne, played in its entirety on the record,is unusual in that it retains the structure of the bransle double throughout all ten dances.

The volta was a vigorous form of galliard in which the woman was thrown high into the air. The particular volta performed on this record is a type of musical pun,for the music is completely danceable in triple time (usual for a volta), but the phrase structure of the music is in quadruple and quintuple time. In this performance,the triple meter is played by the drum. — Lyle Nordstrom

Important Shipping Alert

Due to the pandemic, we are unable to ship to the following countries:

| Algeria | Curaçao | Lebanon | Saudi Arabia |

| Angola | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Lesotho | Senegal |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Dominican Republic | Liberia | Seychelles |

| Argentina | Egypt | Libya | Sierra Leone |

| Aruba | Estonia | Malawi | Sint Maarten |

| Azerbaijan | Ethopia | Maldives | Solomon Islands |

| Bahamas | Faroe Island | Mauritania | South Africa |

| Bahrain | Fiji | Mauritius | South Sudan |

| Bangladesh | French Polynesia | Moldova | Sri Lanka |

| Barbados | Gambia | Mongolia | Sudan |

| Belize | Ghana | Montenegro | Suriname |

| Benin | Grenada | Morocco | Swaziland (Eswatini) |

| Bermuda | Guatemala | Mozambique | Tajikistan |

| Bolivia | Guinea Bissau | Nepal | Tansania |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Guyana | New Caledonia | Timor-Leste |

| Botswana | Haiti | Nicaragua | Tonga |

| Burkina Faso | Honduras | Nigeria | Trinidad & Tobago |

| Burundi | India | Oman | Tunisia |

| Cameroon | Iraq | Pakistan | Turks & Caicos |

| Cape Verde | Israel | Papua New Guinea | Uganda |

| Cayman Islands | Jamaica | Paraguay | United Arab Eminates |

| Chad | Kazakhstan | Peru | Uruguay |

| Chile | Kenya | Philippines | Vanuatu |

| Colombia | Kiribati | Qatar | Venezuela |

| Cook Islands | Kuwait | Republic of Congo | Yemen |

| Costa Rica | Kyrgyzstan | Rwanda | Zambia |

| Cuba | Laos | Samoa | Zimbabwe |

Please see USPS International Outbound Service Outages due to COVID for updates.